Helping Vermonters Find Support with LINK~VT

Link~VT is a new platform being developed for Vermont’s Department of Labor as a part of the VT-RETAIN initiative, which focuses on “preventing work disability and supporting the health and work ability of people who live or work in Vermont”. Its purpose is straightforward: to help residents with disabilities connect with work-disability coaches and find government programs that fit their needs. The system brings together resources from multiple state agencies and allows users to describe their situation, receive guidance, and explore support options in one place.

This term, I’ve worked on LINK-VT as part of the DALI Lab at Dartmouth — a student design and development lab that builds real products for partners. The DALI team was responsible for turning a loose idea (“make it easier for people to find the right help”) into an application that coaches and residents could actually use.

I joined this project during it’s second term of development; the first part of the functionality, storing and accessing resources, had been built by a previous team. Together with two other developers, our tasks this term (to be built in ~3 months) were to:

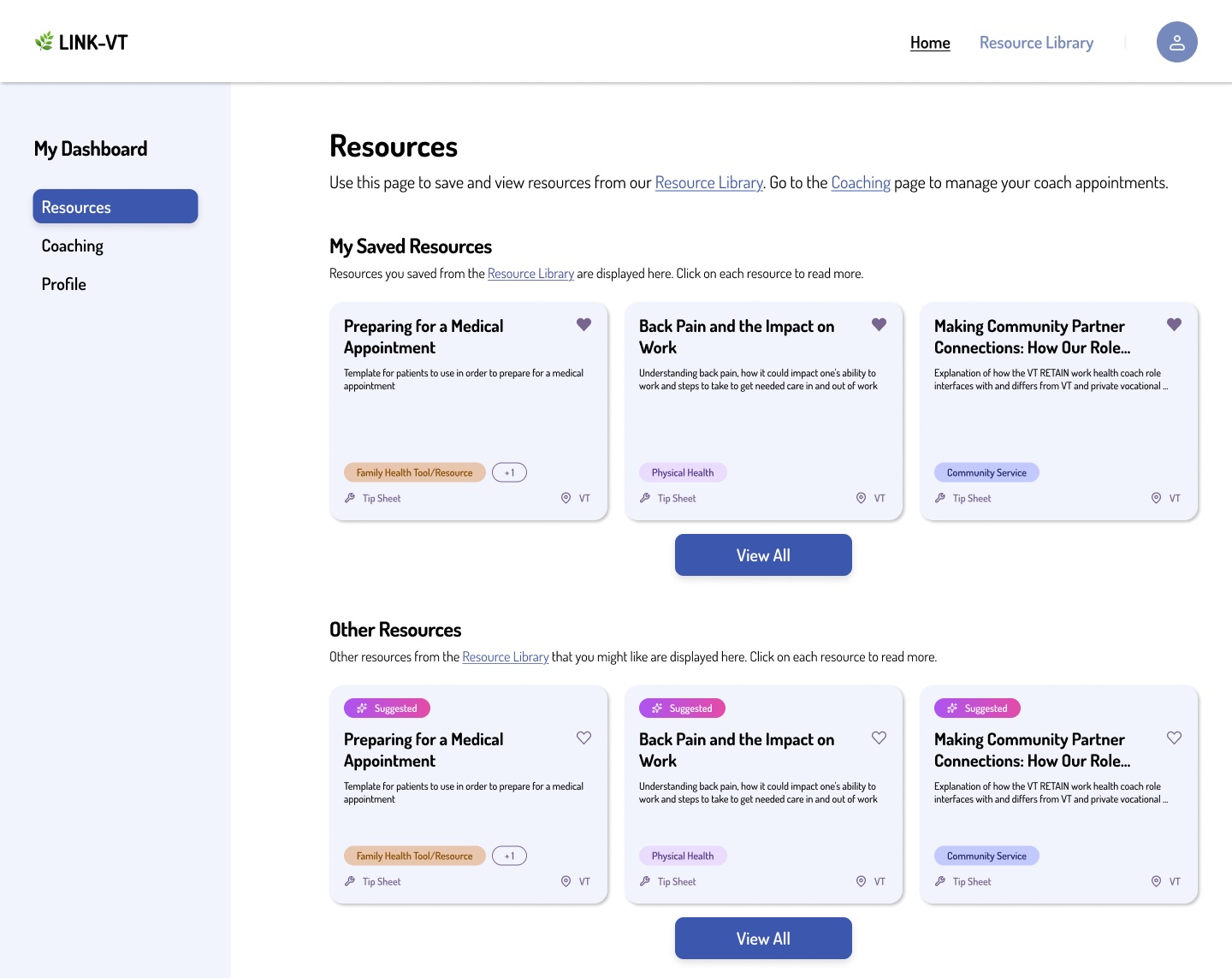

- Build a patient dashboard, allowing users to save resources and schedule meetings with a coach

- Build a coach dashboard, where coaches can upload resources & manage upcoming meetings

- Build an admin dashboard, where new coaches could be registered and patients approved

- Create a pairing system to assign users to coaches

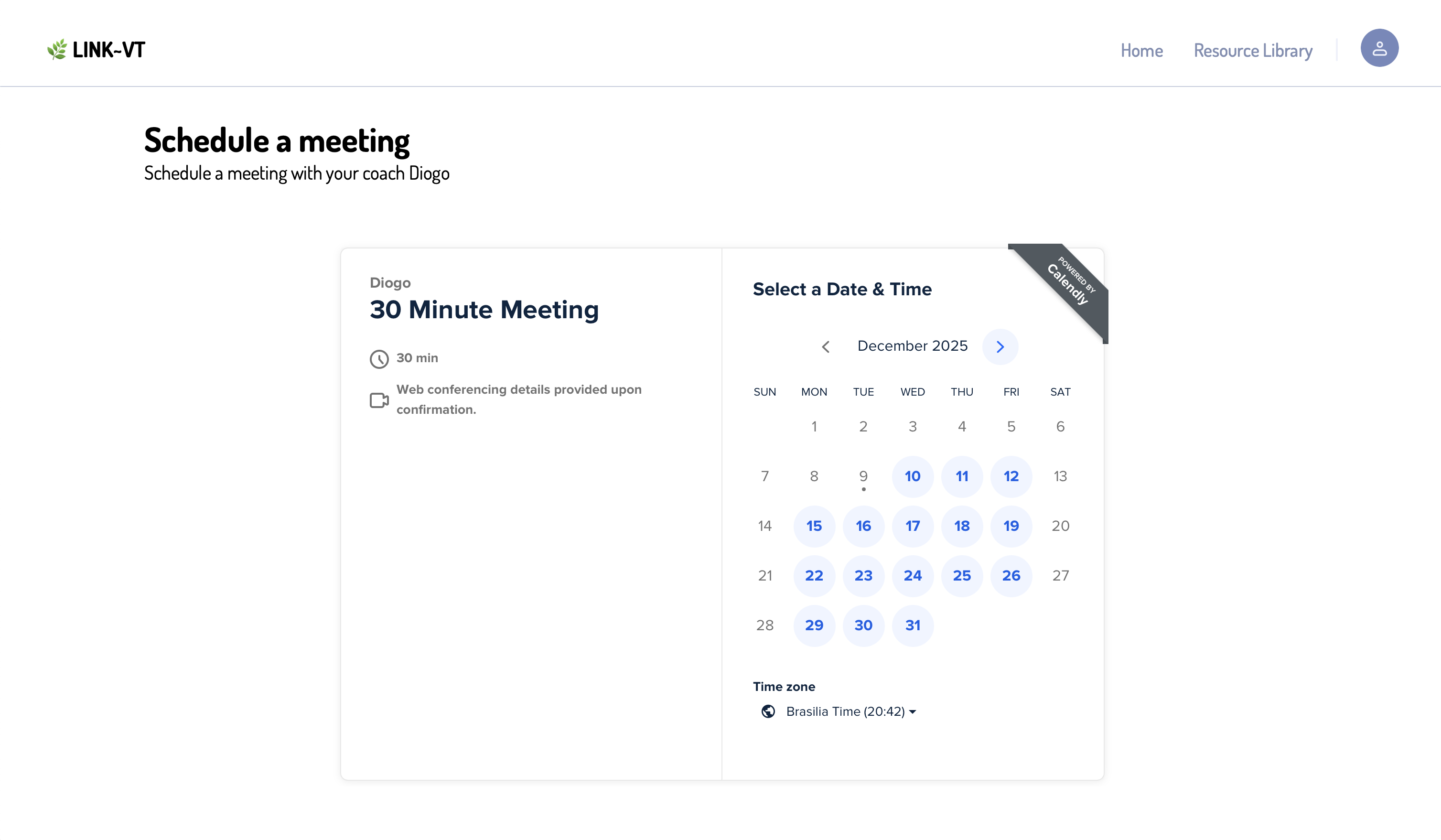

- Create a scheduling system so users could meet with coaches

- Recommend relevant resources to the users automatically

Having spent the previous summer working on semantic search systems (which I wrote about in this post), I immediately gravitated toward the sixth task: making resource recommendations actually feel helpful. At the same time, I took on the scheduling system, which turned out to be more involved than it looked at first.

With those responsibilities in mind, here’s how we turned LINK-VT from a collection of ideas into something residents and coaches can actually use:

0. Building a backend

Before we could build anything intelligent — we needed a backend that could actually support it. The previous team stored resources in Directus, a headless CMS that which was fine for the inital scope, but too limited once we needed:

- role-based access (patient vs. coach vs. admin)

- custom data flows for coach–patient pairing

- API integrations for patient scheduling

- customized resource recommendation

- an approval flow for new resource uplodas

So the first major task for our three-developer team was to migrate everything to a custom Express.js + MongoDB backend. That meant rebuilding the data model from scratch and replacing every piece of logic that Directus had previously handled for free.

Most of the project’s later features depended on these relationships being clean and efficient, so a lot of our early work involved getting the structure right: deciding how to nest vs. reference data, which fields needed indexing, and which operations should be atomic.

This first push took a lot of collaborative effort between the devs on the team. And, once the backend was stable — users could log in, and dashboards could fetch data — we could finally move on to the two systems I owned: recommendations and scheduling.

1. A Recommendation System: The Problem

Our partner organizations initially envisioned a massive, multi-page intake form. Users would check boxes for every category of disability, barrier, or need: “chronic pain”, “mobility limitation”, “substance-use recovery”, “transportation issues”, “difficulty with executive function”, … The idea was to match these to similar tags on government resources.

Our team eventually realized this checkbox-based approach had three fatal flaws:

-

It didn’t capture people’s full context

Residents rarely describe their situations in neatly separated categories. They explain things like:“I can’t drive because of a recent surgery,”

“My shifts were cut because of flare-ups,”

“I need help keeping track of appointments.”Forcing this into dozens of discrete checkboxes stripped out exactly the nuance that coaches said mattered most.

-

It required an unrealistic amount of manual tagging

The original plan was for coaches (or admins) to hand-label each resource with a very large taxonomy of conditions, needs, eligibility criteria, and program types. With resources coming from multiple coaches — and more added over time — this quickly became unmanageable. It also guaranteed that different people would tag the same program inconsistently. -

It created friction during user onboarding

Residents would have needed to check just as many boxes during signup to “describe” their situation. People want to describe their needs naturally, not decode a classification system invented for the database.

2. Prototyping Vector Embeddings

Having spent the previous summer working on an AI augmented search engine, I was excited to have another real-world application for using vector embeddings. This approach turned out to be a good fit for government resources, because are notoriously inconsistent in how they’re written. My goal was to use semantic search to compare meaning without forcing everything into the same template.

Below is my first prototype of a simple form, which took in a patient health description and generated a list of relevant resources:

The demo used transformers.js with the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model; since it

was meant as a quick-and-dirty prototype, it wasn’t focused on performance

or efficiency, and worked as follows:

- Pull all the resources from MongoDB into memory & generate embeddings for each of them based solely on the content description

- Take the user’s health description from the form & generate an embedding for it using the same model

- Evaluate a kNN search for the closest 10 neighbors

- Rank them by cosine similarity

- Display the ones above a ~0.65 threshold.

Though it was built super quickly, in the span of an afternoon, the prototype was successful in getting the partners’ approval for using this method to recommend results.

3. Solving for Production: Vector Databases

With the approval of the partners for this concept, I moved from working on the

demo to something production-ready. After testing a few options, I settled on

OpenAI’s text-embedding-3-small since it was incredibly affordable, and provided

good results in a subjective human evaluation.

The technical stack for this was intentionally simple: use OpenAI embeddings to turn resource descriptions into vectors, then implement MongoDB Atlas Vector Search for fast k-nearest-neighbor lookups based on patient descriptions.

Two design decisions made this reliable in production:

-

Chunking vs. whole-document embeddings

Some resources contained long explanations, FAQs, and eligibility notes. I tested chunking, but ultimately found that embedding each resource as a whole (using concise summary fields) produced more stable results. -

MongoDB database design

Generating embeddings for resources descriptions isn’t super expensive — but re-generating them unnecessarily is. Thus, in MongoDB, each resource document stored: a vector field (embedding), summary text, full description, metadata, category tags (lightweight, optional, used for filtering)

Now, when a patient created or updated their health description in their profile, a small chain of steps kicks off:

- User input is embedded on the fly using the same model.

- MongoDB Atlas performs a kNN vector search, returning the closest-meaning resources.

- We apply lightweight re-ranking rules: surface things a resident is eligible for, prioritize local resources, include category hints when helpful

These resources are then stored in the patient profile, and automatically display in the Patient dashboard, fulfilling the partner’s original vision:

4. Calendar Scheduling

The other system I took on this term was scheduling. Coaches needed an easy way for patients to book time with them, and we didn’t want to rebuild calendars, reminders, and video links from scratch. After trying a couple of options, I landed on Calendly. It handled the parts we didn’t want to maintain ourselves (Zoom link generation, Google Calendar syncing, email notifications) and gave us a clean API to work with.

The final workflow on was straightforward:

-

Connecting coach accounts with OAuth

Coaches authenticate through Calendly’s OAuth flow, and our server receives a small set of read-only permissions. We only request what we actually need: the coach’s event types and the meetings booked through those event types. The access + refresh tokens are stored on our side in encrypted form. -

Using limited-scope credentials to read availability

Once a coach is linked, we can fetch their public event types — essentially the windows they’ve made available for LINK~VT appointments. This lets patients schedule directly inside the app without the coach doing any extra setup. -

Capturing scheduled meetings

We poll Calendly when a user schedules a meeting and store the resulting meeting ID in MongoDB. We associate the meeting ID with both the patient and coach. Using the Calendly API we fetch detailed information & current status for the meeting. We memoize these results, so dashboards don’t block on external API calls. As long as the data hasn’t changed, we serve it instantly from memory. -

Showing upcoming meetings

With meeting records stored locally, surfacing them in dashboards became trivial. Patients get a simple “Your next meeting” card with date, time, and Zoom link. Coaches see a list of all upcoming sessions in their schedule, and admins can confirm that new coaches are set up correctly.

This approach ended up being low-friction on all sides: coaches keep using whatever calendar setup they already have, patients can book help in a couple of clicks, and our backend stays simple and predictable.

Takeaways

To me, working on LINK~VT has been especially valuable because it let me take technical concepts I’d been experimenting with on my own and use them in a situation where real people would depend on them. It forced me to think about whether the tools I liked in theory actually held up when someone needed the system to be clear, fast, and not get in their way. The connection between tech & the user experience made the project feel more substantial and I look forward to hearing feedback about the LINK~VT trial run in the upcoming year.